“BUDDHA IS SUPREME”

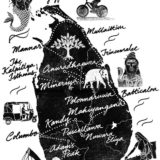

In keeping with their religious beliefs, the Buddhists were preparing to celebrate the full moon day of May 1918 in all its traditional splendour. In the Buddhist calendar, it is the day set aside to commemorate the three most sacred events in the life of Buddha – his birth, his Enlightenment and his passing away. This holiest day of the Buddhists is known to the Sri Lankan Buddhists as Wesak.

Apart from religious observances, the common practice was to turn the night into a festival of lights. The full moon, the hand-made lanterns and the wild electric beauty compete with each other to illuminate the life and compassion of the Enlightened One. The wide-eyed devotees flock to the city centres to be mesmerized by the episodes in the life of Buddha bursting with dazzling electric energy. The generosity of the Buddhists overflows with offerings of food and drinks to the villagers swarming all over the city.

In Colombo preparations were being made to receive the usual concourse of Buddhists pouring into the city from remote villages. But the dawn of Wesak on May 24, 1918 was rather gloomy. It turned out to be the wettest day of the year. The Wesak devotees’ spirits were dampened by the intermittent showers. Besides, the trains bringing the Buddhists from the villages too were reduced by the British Raj. The abundant rains and the reduced trains kept away the crowds that usually thronged the streets of Colombo for Wesak.

Wesak celebrations of 1918 were also marred by an imperious act that did not pass away like the showers of rain. The District Judge of Chilaw, Mr. Carbery, was at the centre of this storm. In Puttalam he objected to a banner that said BUDDHA IS SUPREME and ordered it to be pulled down. This banner was displayed prominently on a bus. The Police Sub-Inspector carried out the order promptly.

The reaction to this provocative act was spontaneous. It became the most controversial issue in the days after Wesak. The Ceylon Independent headlined it as “The Puttalam ‘Bus Incident.”[1] Obviously, Mr. Carbery’s religious sensibilities, which were inextricably intertwined with his imperial mission, had been offended. He had objected to the banner being “glaringly displayed” on the bus. The Editor of The Ceylon Independent took a different view. He said: “….we do not see anything aggressive in it. It is merely an expression of a devotee’s faith.”[2]

Mr. Carbery was a typical representative of the British raj who was driven by the doctrine of white supremacy. The British apparatchiks, who ran the far-flung Empire in distant posts, were imbued with this sense of superiority that invariably conflicted with the inherited culture of the lands they occupied. Though the British did not pursue racist policies overtly they asserted their racial superiority discreetly through their hegemonic politics administered through the legislature, judiciary, the bureaucracy and, of course, the police. These arms of the British raj brooked no serious political challenge from the coloured natives, whether it came from a religious poster on a bus or a temperance movement. Earlier, in 1915, the panic-stricken British either shot or incarcerated the Sinhala-Buddhist leaders of the temperance movement, fearing that it was an insidious political agitation against the British rule.

In planting their flag on territories that did not belong to them they assumed that it was the white man’s burden to liberate the non-whites. The colonialists, wherever they went, fervently believed that it was their divine mission to civilize the natives. This was a common justification advanced for wielding power over the natives by the colonialists from the West. To them the natives were, by and large, lazy, barbaric, untruthful, untrustworthy and needed the discipline of their white masters to make them productive not so much for their good but for the expanding markets of the West. If they had something nice to say about the natives it was expressed in a patronizing way to offer backhanded compliments only to those who had served them obediently. Their judgments depended entirely on the merits or demerits of the natives’ contributions to their economic and political interests.

And these condescending judgments were not confined to the ruling elite only. Some of the most severe judgments were handed down by those who came as missionaries to serve the humane values of Christianity. For instance, Rev. H. W. Cave, who arrived in Ceylon (as it was known then) as private secretary to the Bishop of Colombo wrote: “The Tamil coolie may be a shocking barbarian in point of intellect and civilization as compared with his British master, but making allowances for his origin and opportunities he is by no means an unfortunate or contemptible character.” [3] The patronizing superiority of the prevailing Christian attitude reflects the unfortunate and contemptible character of Rev. Cave more than the non-white “barbarians” he hoped to civilize. Not surprisingly, William Sabonadiere, a coffee planter, went the further and said: “Untruthfulness comes as naturally to a Tamil as mother’s milk.” [4]

The hidden agenda in civilizing the natives was to tame them and make them obedient to their political will. In fairness to the British, it must be mentioned that of the three Western colonial powers that came to Sri Lanka — the Portuguese (1505), the Dutch (1658), and the British (1796) – the last was the most liberal. The Catholic Portuguese and the Protestant Dutch brought with them their religious bigotry and persecution to Sri Lanka. They persecuted not only non-Christian heathens (which included Muslims) but also Christians who did not belong to ruling denomination.

The Dutch Governor, Ryclof van Goens, wrote on July 16, 1661 :“All heathen and Muhammadan superstitions must be rooted out in this country as far as possible”.[5] The Dutch Protestants’ hatred of Roman Catholics and the political rivalry between the two sea-faring nations led him to write: “That with a view to root out the impious and evil practices of the Portuguese, the customs of our Fatherland must be introduced. That to this end must from time to time be transported from the country all Portuguese who vilify and despise our customs and religion.”[6]

The first British Governor, Fredrick North, initially attempted to go down the track of state sponsored religion. All schools were under the Anglican clergymen. When North imposed the Joy Tax which meant paying a tax for wearing jewelry it was the school girls that were affected most. Parents refused to send their girls to school as it was too costly. Petitions urging the repeal of Joy Tax were rejected. It was left to his successor, Sir. Thomas Maitland, to remove the tax.

Subsequently, the British raj restored religious liberty that prevailed in the pre-colonial days of Sinhala rule. This does not mean that the British raj was either neutral or adhered to the Kandyan Convention in which they pledged to protect the religion of the Buddhists. [7] Unofficial patronage to Christians, based partly on the assumption of superior values of the West and partly on the need for an ideological fifth column loyal to the raj, permeated the minds of British officials like Carbery. The British rulers refrained from the suppression of other faiths because the destructive internecine Christian wars in England had chastened and liberalized them. Besides, religious tolerance was good for the maintenance of law and order. It reduced one less burden on their imperialistic regime. However, the overarching superior attitude of the white Christian rulers threatened to undermine the essential spirit of the nation.

Mr. Carbery’s action was, no doubt, an embarrassment to the British establishment. But the Acting Governor, R. E. Stubbs, played it down by ignoring it. This did not pacify the rising English-educated, Sinhala middle-class that was challenging the British raj in their quiet, measured style. They censured him publicly. Mr. Carbery, no doubt, had carried his imperial attitudes too far. The subsequent furore in the press reflected the undercurrent of tensions between the majority Sinhala-Buddhists and their imperial masters. The Manager of the bus company questioned Mr. Carbery’s authority to remove the banner. A correspondent who signed as “W. R.S” asked why the native prohibitionist should not have the same right as the white Magistrate to pull down liquor advertisements displayed on the city trams.

It was J.H.P. Wijesinghe, another correspondent, who exposed the attitudinal problem of Carbery. Outlining his experiences with Mr. Carbery, he wrote: “Mr. Rodrigo, the well-known advocate of Negombo and I were seated in a first-class compartment of the Negombo train at Maradana Station. Mr. Carbery, the District Judge of Chilaw, Mrs. Carbery, their child and a European nurse entered it. Then a Sinhalese young man entered the first-class compartment. Carbery promptly asked him, in a manner not too conciliatory, whether he had a first-class ticket. The man replied: “If I had not a first-class ticket I would not have come in here,” and proceeded to sit beside Mrs. Carbery. Carbery then invited that lady to change her seat and in the same breath informed the young man that he was the District Judge of Chilaw and that he disliked impertinence.” Wijesinghe added: “To judge from his agitation, language and manner it was obvious that Mr. Carbery objected to natives in the first-class.”[8]

The rising Sinhala middle-class in the early decades of the 20th century was facing the brunt of most of the low-intensity confrontations with the British raj. Armed with the power of the English language – the medium of the ruling masters — and a pride in their own ancient culture, dating back to the times when the British were nomadic tribes, they felt that they were equal to their white rulers, if not superior. Barring a few enlightened Britishers, the ruling elite hardly accepted this notion of equality. Their social attitudes were determined by their political assumptions that the natives were not fit to govern themselves – at least not in 1918.

The British policy was to absorb the rising elite into the lower levels of the political system without making them their equals by handing over too much power. Keeping the distance was essential for them to wield total power. This was expressed unambiguously in social segregation. Their superiority was expressed in carving out “WHITES ONLY” enclaves. They resented the intrusion of the natives into the privileged domains of the whites. One of this was the first class carriage in railways – the mode of public transport categorized on a class basis. The panjandrums of the raj often clashed with the natives in the first class carriages.

In India, where white supremacists were lording it over the coloured natives, white-non-white clashes due to this unofficial segregation was a common occurrence. Annie Besant, the anti-British English firebrand who was a pioneer of the swaraj movement, exposed the injustices inflicted on the helpless Indians. “On the 19th and 20th January, 1910,” wrote Annie Besant, “the Central Hindu College (of Benares) held its anniversary and Old Boys came from every part of the country to renew the feelings of their college days and to show their love for their Alma Mater. One of these, a young man with a brilliant record behind him, having taken his ticket, entered, as was his right, a railway carriage for Benares. An Englishman was already in it and as the young Indian gentleman was entering, this person roared at him: “Get out, you Indian dog!” The student was frail in body and small in stature, and could not fight the bully, as another might have done. He went to another carriage…….”

Then in an appeal to her compatriots she said: “And you, who are our Rulers in this land, you may ask: “Why does not the Indian appeal to the law when he is outraged? Because, alas, though justice is done between Indian and Indian, it is not done between the Indian and Englishman. When a little time ago, an Englishman kicked away an Indian, who pleadingly caught his feet in Indian prayer for pity, and the Indian died, the slayer, an official, escaped with a fine. The Indian shrinks from seeking the protection of the law, because he does not believe that it will protect him.”[9]

The first class carriages of British-government-owned trains turned out to be a domain of the white supremacists. This exclusiveness, amounting to segregation, and the insistence of the natives to share public utilities were two opposing political statements that were loaded with a potential for instant clashes. F. H. Dias Bandaranaike of Castle Street, Borella, for instance, was assaulted by two Englishmen whilst travelling to Mirigama in the first-class compartment with his wife and children. One Englishmen held him while the other bashed him up. When he sued the assailant, M. V. Clapham, the magistrate acquitted the white man and fined Bandaranaike for perjury.[10] Racist supremacists of the British Raj knew how to bend the rules to favour their own kind.

Earlier the Sinhalese had felt the full force of British brutality in the riots of 1915. The excesses of the British government in handling a storm in a tea cup were symptomatic of their paranoia. The British were paranoid about the Sinhalese who happened to be the only community that rebelled against their rule. Compliant Jaffna never raised a rebellious flag against the British.

All in all, the early years of the 20th century did not augur well for the Sinhalese. Of the minority communities the Burghers, who were the descendants of the Portugese and the Dutch colonialists, were safely ensconced in the British hierarchy. The Jaffna Tamils, in exchange for their loyalty, were given a nudge-and-a-wink by the British to pursue their insular politics and their casteist life-style that dominated the peninsula. The Muslims were left to remain where they were – at the lowest rung of the ladder without any significant social mobility. The Indian coolies were imported as a breed of lesser human beings and left behind by the British in inhuman conditions in the plantations that sustained the British Empire.

The indentured Indian coolies, exported from India as cheap labour to various corners of the far-flung Empire, were worked to the bone to add glory to the expanding commercial enterprise of the raj. The land occupied by the advancing British forces had no value in itself unless cheap labour was introduced to add value. There was no glory in the conquests unless profits were reaped from productive land. There is neither profit nor glory in barren or fallow land. The Indian coolie was transported to make the fallow and the barren land productive for British enterprise. They cleared and tilled the land, planted tea, coffee or coco and carried the harvests on their backs for a mere pittance.

The British Empire was carried on the backs of these homeless, helpless armies of immigrants transplanted in alien countries. The British harvested the profits and fled leaving these migrants in hovels unfit for human habitation. The irony is that, after inflicting all the suffering the British moralists and their NGO agents now accuse the succeeding post-independent governments of denying the Indian workers their due rights.

A significant part of the process of decolonization meant coping with the grim misery left behind by the British wherever they went. Politically, however, it was the Sinhala-Buddhists who faced the brunt of both colonization and decolonization. During colonial times they were suppressed and denied their rights because imperialism depended on denying the rights of the people. During the post-colonial period, when they started to redress the historical imbalances and injustices left behind by the colonial masters, the people were once again denied their right to reclaim their historical legacy by those who inherited privileged positions, perks and power from the departing colonial masters. Like their colonial masters the native remnants left behind also depended on denying the people their birth rights.

The privileged English-speaking minority who ruled the roost in the post-colonial era fought back to retain their powers and privileges they inherited from colonial times. They resisted changes to the old order that would diminish their status. The English-speaking minority like the colonialists believed that their privileged position deserve exclusive domains to preserve the purity of their linguistic/ethnic superiority. Both concocted ideologies, rituals and rules to exclude the non-English-speaking “other”. Anyone posing a threat to their assumed superiority, purity or privileges had to face violent consequences like being thrashed in the first class carriages of the British railways.

Even in Jaffna it was the English-speaking Vellahla elite that oppressed the non-English-speaking low-castes. They controlled and manipulated the socio-religio-political culture to their advantage. It is this elite that of was behind the Vadukoddai Resolution that unleashed the Vadukoddai War. The non-English-speaking low castes were mobilized to fight the war launched by the English-speaking Vellahla elite. And when the war was escalating the English-speaking Tamil elite left for greener pastures abroad leaving the non-English speaking mob to carry the burden of the Vellahla war.

In short, colonialism did not end when the colonial masters left the island. The Anglicized and the English-speaking elite left behind in privileged positions in the public and private sectors were determined to retain the old colonial order and continue from the places where their old colonial masters had left as if no changes had taken place. Getting rid of colonialism and its privileges caused most of the political tensions in the post-independence period.

Sri Lanka is still battling colonialism even after 66 years of independence. The Vadukoddai War, for instance, could have been hailed as the final act of cleaning up the messy colonial past and restoring the new order in which the victims of colonialism would have new opportunities to regain the lost heritage. Unfortunately, instead of Carbery the nation is now facing Cameron. Though they are two different characters in two different ages the arrogance is the same.

So do we fight or do we surrender?

Footnotes:

[1] The Ceylon Independent, May 31, 1918 – p.1.

[2] Ibid.

[3] H. W. Cave, Golden Tips (Cassel, London 1904) cited by Donovan Moldrich in Bitter Berry Bondage, The nineteenth century coffee workers of Sri Lanka, – p.VI,

[4] Ibid – p.VI, cited from William Sabonadiere, The Coffee Planter of Ceylon (Guernsey, UK, 1806) p.86.

[5] Memoirs and Instructions of Dutch Governors, Commandeurs and etc, translated by Sophia Pieters, Government Printer, Ceylon 1908 – p. 81

[6] Ibid – p.7.

[7] Article 5 of the Kandyan Convention declared Buddhism inviolable, and promised the maintenance and protection of its rites, priests and temples. But once the British consolidated their grip they abandoned their commitment to Article 5.

[8] The Ceylon Independent, June 3, 1918 – p.1

[9] The Ceylon Patriot, March 1, 1910 – p.4. “An Appeal to the Government and the Europeans” by Annie Besant, President of the Theosophical Society and of the Central Hindu College, Benares.

[10] The Ceylon Independent, June 8, 1918 – p.1